From pre-K to the working world, our bodies are guided and governed by an ever-changing but ever-present set of rules: the dress code.

When students are as young as kindergarten, around six years old, they are already told what they can and cannot wear, and the code—both sanctioned and unspoken—doesn’t ever go away.

When I was 18, I started a job at a grocery store chain. During employee orientation, the trainers handed out nicely-bound rule books and policy manuals. In the section on the dress code, there were two paragraphs: one outlining rules about ponytails, spaghetti straps, and nail polish and a second on armpit hair and body odor. I couldn’t help but wonder why the company decided to organize the list of rules this way. They could have written the rules in one long paragraph. They could have been broken up based on clothes and hygiene. Instead, there were just two paragraphs…and it certainly seemed like one of them was targeting my gender and the other wasn’t.

Aside from the assumptions embedded here concerning what an average man and an average woman look like, there was something else that got my attention … One paragraph was twice as long as the other one!

There were twice as many rules in the section of the dress code that seemed to be regulating women’s appearance as the rules that seemed to apply to their men coworkers. Here are a few examples:

No visible armpit hair.

Limited facial piercings.

Limited visible tattoos.

Hair always pulled back neatly—no wisps or locks falling out!

Straps on all shirts must be “three fingers” wide.

Shorts must reach the bottoms of the fingertips.

No excessive makeup.

No excessive body odor.

No yoga pants; bottoms must have belt loops and back pockets to be considered acceptable.

No fingernail polish.

Some of these apply to all genders, and some I agree with. I won’t argue with rules related to basic food safety and hygiene. But some of these rules I have trouble justifying. Why is it important how wide or thin a woman’s straps might be, or the length of her shorts?

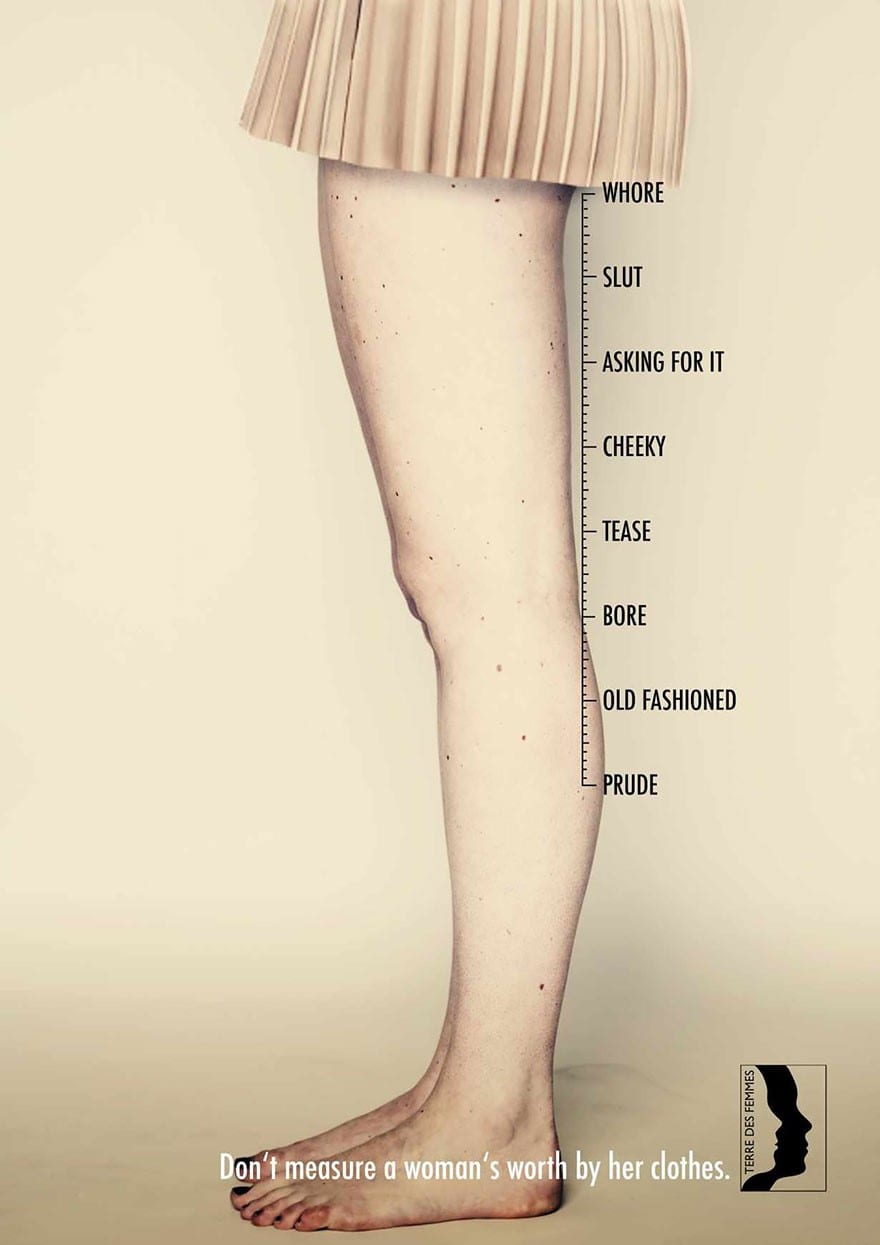

While I could just grumble about not being able to find a single pair of “acceptable” shorts, I choose to look a little deeper and question why so many rules exist in the first place. Could it be because my body, as a woman’s, is seen as inherently sexual, and must be covered to preserve my modesty? Perhaps it is my duty, as a sexual object, to do everything in my power to shield everyone from the distraction that is my physical body.

That is the same logic that contributes to rape culture overall and victim blaming.

When a girl is wearing a low-cut shirt and gets catcalled on the street, what did she expect, wearing something like that?

If she is at a party, wearing that same low-cut shirt, and gets raped, did she expect it then? Was she asking for it?

The dress code is just one small manifestation of rape culture. From the age of six, sometimes younger, girls’ physical appearances and expression are strictly regulated, whether informally, in the victim-blaming comments like the ones above, or formally, with a dress code. The dress code, seemingly insignificant when compared to explicit sexual violence, contributes to the same rape culture that regulates the feminine appearance and asserts that women’s bodies do not belong to them.

Written by Claire Cuthbert, MESA Intern and graduate of CU Boulder in Psychology and Spanish

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.